Maps are great – they are printable and easy to display on screens, and as such portable and easy to use. But they are flat. The geospatial dimension of elevation is mostly obscured in maps – even topographical maps that use contour lines (isohypses) to encode terrain shape make it hard to extract the highs and lows of our environment.

But accurate elevation data are crucial for many applications: establishing viewsheds and line-of-sight modeling for telecommunications towers, understanding hydrology and erosion patterns in agriculture or urban planning, or estimating flood risks for insurance companies, to name a few.

DTM and DSM – Two 'flavors' of Digital Elevation Models

For businesses and administrations relying on such geospatial data, the solution is Digital Elevation Models which are created from a variety of inputs. Radar data like Synthetic Aperture Radar, airborne laser altimetry (LiDAR), stereo and tri-stereo imagery, and ground-based measurements (relying on GPS or traditional land surveying are used to create datasets that can be plugged into Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

The models come in essentially two types:

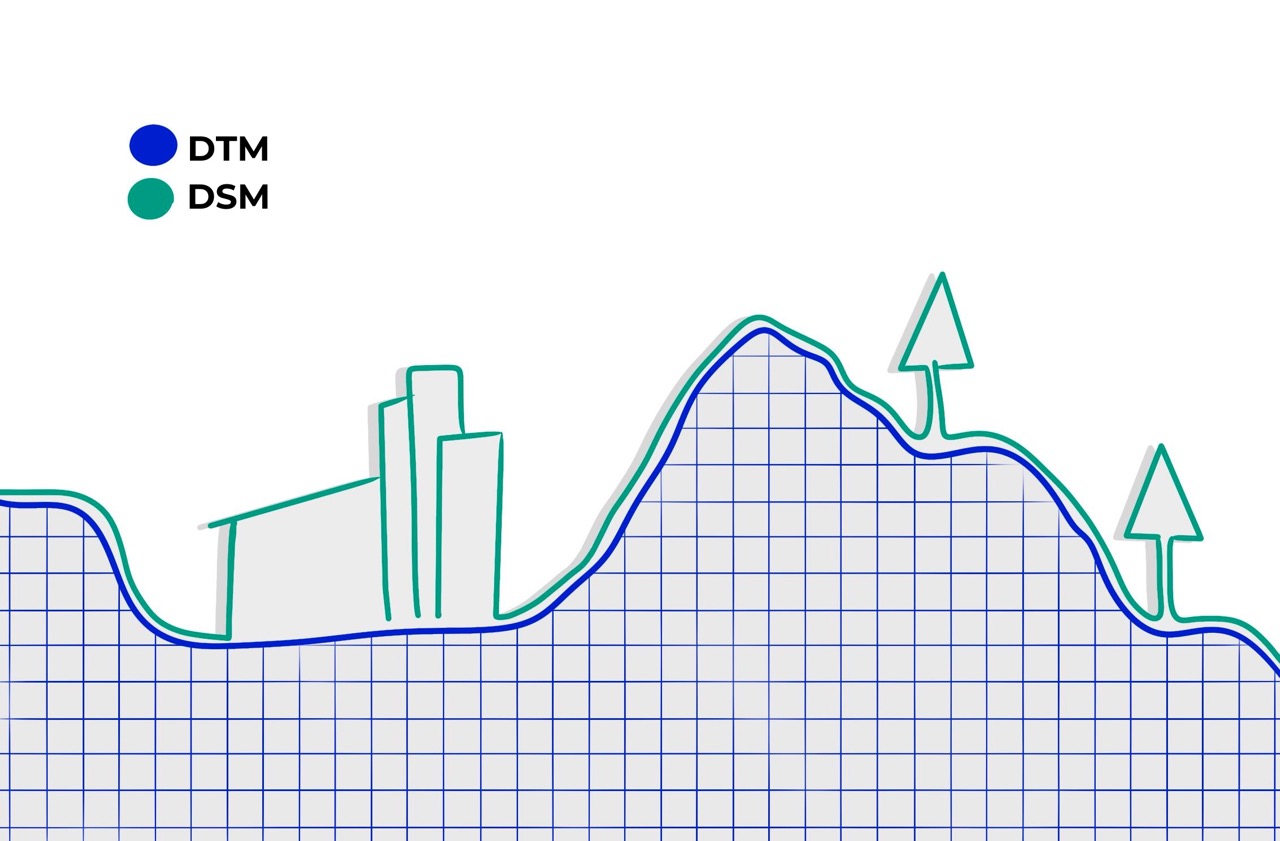

Digital Surface Models (DSM), which get as close to a true view from above as possible, modeling the top surfaces of vegetation and human-made structures.

Digital Terrain Models (DTM), on the other hand, show only the natural elevation contours; for this “bare earth” model, vegetation and buildings are digitally removed – a process that is often computationally heavy and can be challenging, particularly in large and densely populated urban areas.

While there is no universally acknowledged textbook definition, the term “Digital Elevation Models” (DEM) is mainly used as the generic name for both DTM and DSM.

One of the most extensive missions to create Digital Elevation Models of the earth was launched in February 2000, when the Space Shuttle Endeavour (STS-99) flew its “Space Shuttle Radar Topography Mission” (SRTM): Over 11 days, Endeavour orbited the earth 16 times and covered 83 Percent of its surface, from 56° southern latitude to 60° northern latitude; the data from its two-antenna interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) allowed to create digital elevation models in a resolution of 30 meters, with vertical accuracy around 15 meters. The United States Geological Service (USGS) eventually made the entire datasets freely available for download by everyone by 2015.